Check our opening times and prices

Buy your ticket in advance

Prepare your visit to the battlefield

The Battle of Verdun began at 7.15am on 21 February 1916 with an artillery bombardment that rained down on the forts and trenches. The German Chief of Staff, Erich von Falkenhayn, wanted to put an end to the war of positions that had been going on since the Battle of the Marne began 18 months earlier.

In late 1915, General von Falkenhayn, who had become head of the German army in mid-September 1914, decided to attack the French at Verdun. From the time he took command, von Falkenhayn was convinced that Germany, faced with a war of attrition in both western and eastern Europe, could not win on the basis of its military strength alone. To prevail, it would need diplomatic action based on military successes that forced its enemies to sign separate peace agreements. He saw Germany’s main adversary in the war not as France, but as its ally Britain. His aim was to beat the French before dealing with the British. The decision to attack France was a response to the weakening of the French army as a result of the heavy losses of 1914 and 1915. (At this point, French losses since the outbreak of war totalled 700,000.) Von Falkenhayn also believed that the conflict had shaken the French Republic, leaving it in crisis, and that a major military defeat would prompt politicians to seek peace.

On 30 November 1915, von Falkenhayn announced to his top commanders that the focus in 1916 would be on the western front. Initially, he intended to attack the French front outside Belfort, but in mid-December 1915, General Schmidt von Knobelsdorf, chief of staff to the Crown Prince, the commander of the 5th German Army that was fighting in the Verdun sector, persuaded him to attack there.

In his memoires, written after the war, von Falkenhayn claimed that the aim of the offensive against Verdun was to bleed the French army dry, by which he meant inflicting the maximum possible losses under the “meat grinder” of the thousands of shells that would be fired. Specialists continue to debate the question.

The 5th German Army was to lead the offensive. It was reinforced with additional units in preparation for the attack. From late December 1915, every day numerous trains ran along the Valenciennes-Hirson-Mézières-Thionville line bringing thousands of men and large quantities of equipment. Infantry battalions and artillery batteries filled the numerous roads of north-west Lorraine, converging on the lines outside Verdun. By the last few days of the year, two army corps were ready to engage outside Verdun: the 5th and 7th Reserve Corps.

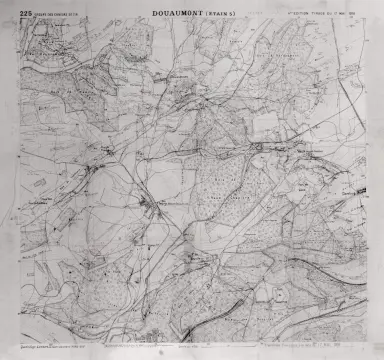

Losses totalled 163,000 dead and 216,000 injured on the French side and 143,000 dead and 190,000 injured on the German side, making a total of almost 700,000 killed or injured on the Verdun Battlefield in 1916. Nine villages (Fleury, Bezonvaux, Haumont, Beaumont, Cumières, Vaux, Ornes, Louvemont and Douaumont) were completely destroyed and never rebuilt. These villages were declared to have “died for France”. The Douaumont Ossuary, housing the remains of 130,000 soldiers, and the cemetery that stretches in front of it with more than 16,000 graves are the most dreadful and stirring representations of the hecatomb of 1916 in Verdun. The destroyed village of Fleury-devant-Douaumont, of which not a single stone was left standing, remains one of the most terrifying demonstrations of the destructive weapons unleashed during the First World War.